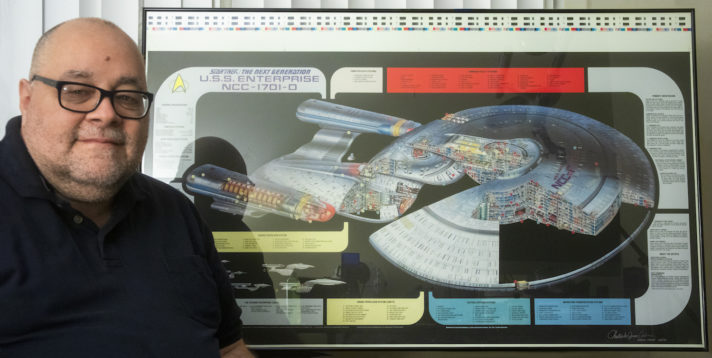

Christopher Cushman is the illustrator behind some of Sci-Fi’s most iconic and notable cutaway illustrations.

He reached out to share some of his obsessively accurate and detailed artwork, and the story of how a chance encounter with the legendary David Kimble turned from a freelance gig, to a prolific career in Detroit’s auto industry—to illustrating vehicles from the 24th century, and some from a long, long time ago, too!

What drew you to cutaways and technical illustration?

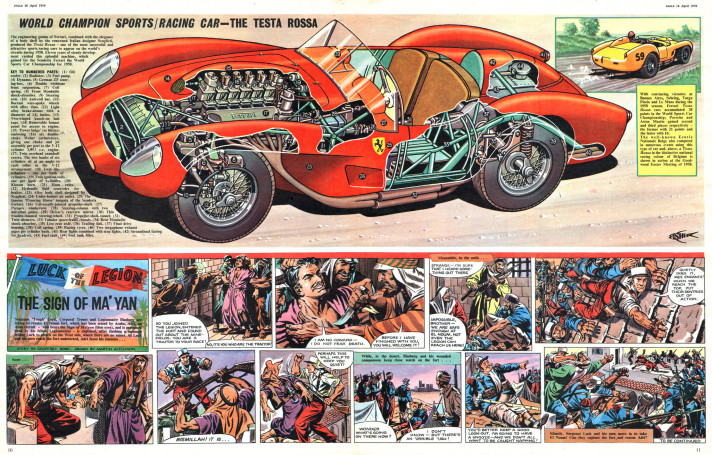

Sometimes I think all roads lead from Star Trek… I became interested in technical drawings when I got my first blueprint set of the Enterprise by Franz Joseph. They literally explained the entire ship deck-by-deck with hundreds of details. This was around 1975—I was 15. It was amazing to me that drawings could convey an understanding all on their own!

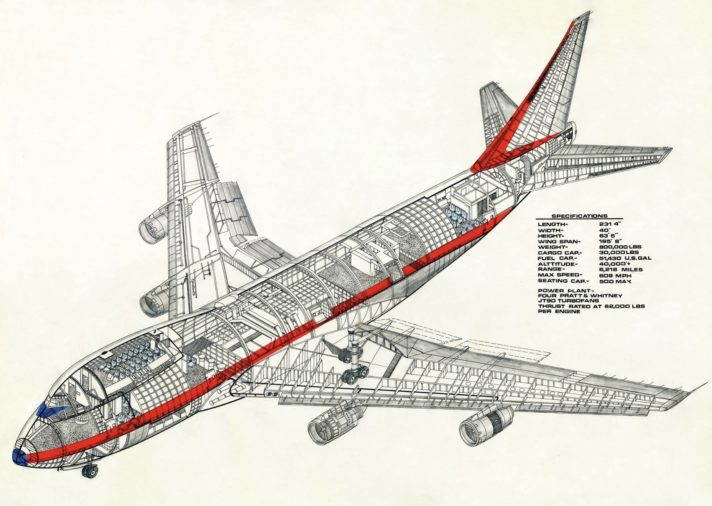

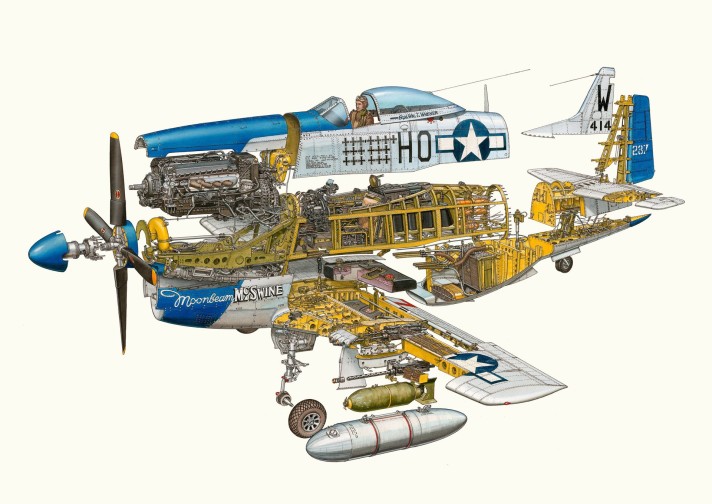

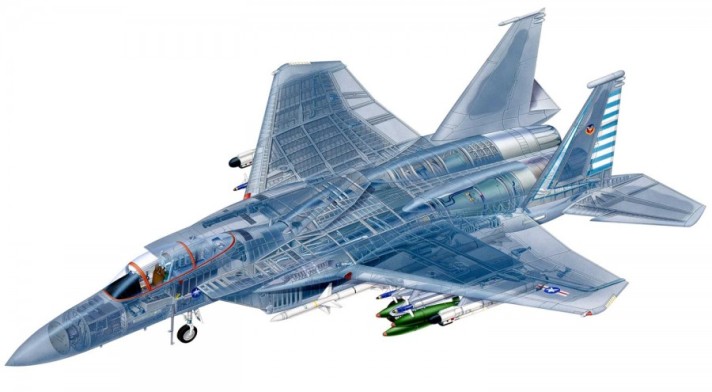

In high school I had a teacher named Mr. Moll who encouraged me to become a technical illustrator. He suggested that I enter a state wide competition, the Michigan Industrial Education Awards. This was my senior year and it was a go big or go home moment, so over summer break I wrote Boeing in Washington state to get blue prints and anything related to their 747. I received a package a week before school started and over the course of that year I drew my first cut away of a 747. It received the regional honor award, and the highest award for my school that year.

I was hooked!

How did you learn the skills of technical illustration?

The following year I went to Ferris State in Big Rapids Michigan. Ferris was unique, in as much as their Technical Illustration program was the most comprehensive in the mid West, and there approach was to build skills and then teach through simulated real world experiences.

The instructors were John James and Doug Farnham, both veterans of the illustration world. Both had different teaching styles. Mr. James was inspirational and really open to a lot of ideas, while Mr. Farnham featured himself a professor and was always very critical. Between the two we were able to experience two different management styles that would be useful in the real world. While much of the training was on technical illustration, we also had classes on graphic design, drafting, engineering principals, material science etc.

In hind sight, that education really paid off for me because so much of my work deeply depended on me to be able to hold engineering conversations with many kinds of specialists, and then translate that into art that would best work for them.

How did you get your illustration career started after school?

So, post-school I bounced around a bit. I got a gig at Mid America Design in Fort Wayne, Indiana designing manuals for the military, including an upgrade ejection seat installation document used by the Indiana Air National Guard. From there, I worked my way back up into Michigan working for Zennith/Heath Kit in St. Joesph. Again, we made manuals for many Heath Kits, which were electronic kits you could buy and assemble—from the super simple all the way up to a 25-inch Zenith TV. One of the projects I was most proud of was a kit to build a personal robot called Hero.

I moved back home and began commuting to Oldsmobile engineering in Lansing, Michigan. The work was great, but the hour plus commute each way was a nightmare, so I made the big leap back to Detroit. I started working for what in the industry were called “job shops,” basically outsourced talent pools that allowed the big three to avoid having to hire themselves.

I settled at a firm called Modern Engineering, where I drew large format drawings that hung in assembly plants called “production aids.” I worked exceedingly hard, and quickly became an expert often called into meetings to explain certain production processes (thanks to that Ferris training).

In one or two meetings I had made process change suggestions that got noticed at GM, and I was seconded to work at the GM Teck Center for the BOC (Buick, Olds, Cadillac Group). My job now was to help funnel projects to the job shops and work with engineers on various challenges. For almost a year I worked directly out of the Detroit Hamtramck Assembly Plant, and was responsible for the entire production lines worth of production aids. Hundreds of drawings that would help them build the all new models of Riviera, Toronado, Eldorado and Seville’s. Towards the end of that assignment we also added the Cadillac Alante to the mix. Needless to say, when I returned back to the technical center the economy was turning and I faced going back to Modern Engineering.

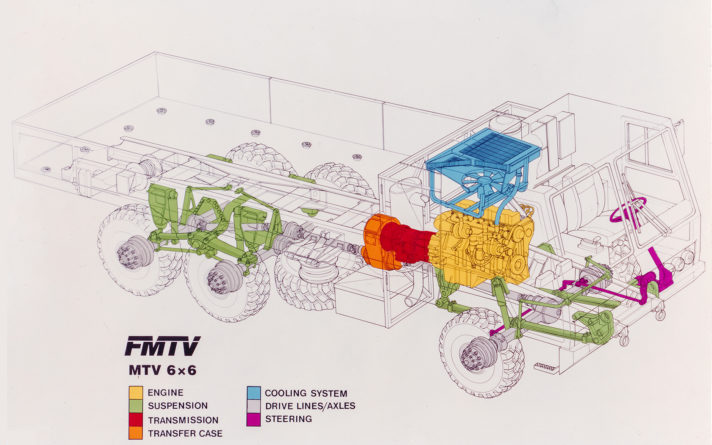

But my years of networking started to pay off and I was able to extend my journey with the GM Military Vehicles group. This was a major leg up in many ways, as the kind of work exceeded just technical illustration and included product development and design, branding, graphic design, video and display design! I quickly garnered the title of Art Director. The one thing was to leverage the opportunity into greater learning opportunities. I got the chance to see one of my concept drawings grow into scale models and then into full size working prototypes with the FMTV Tactical Vehicle Project and the HETS Heavy Equipment Transporter System.

While working at GM, you ran into David Kimble. You became friends, then began working with him. What was that relationship like?

As I previously mentioned the work I did with the BOC had me attending many meetings, one of which was at the offices at the Cadillac Fleetwood Plant on Detroit’s west side. I was waiting in the lobby when two men came in, and one of them rather loudly announced him self as being David Kimble, as if the young lady at the desk should know or care who he was.

What was lost on her was not lost on me, and I must admit I sprung up in true fan boy fashion to introduce myself, got to share what an inspiration he was, blah blah, explained that I too was an illustrator who worked at the Technical Center. He asked if I ever did freelance, and offered that he would love to see my portfolio on his visit to the tech centre the next day as he had a meeting there.

Wow, I didn’t sleep much that night. True to his word he passed by my area, which garnered a lot of attention from the fellas in my group who also held him in esteem. I showed him my work and gave him my card, and within a couple of weeks we were off to the races.

He was very direct and clear with his expectations, and I could tell immediately that he suffered no fools when it came to his work. Many, if not most of the assignments were ink tracings of his drawings. My first assignment included the drawings for the brochures for the first Acura products, the Integra and Legend.

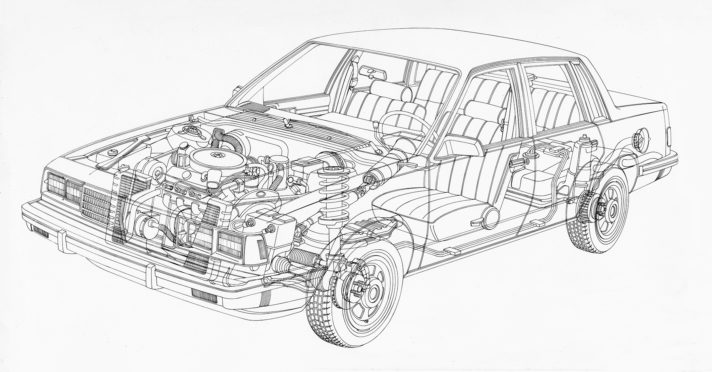

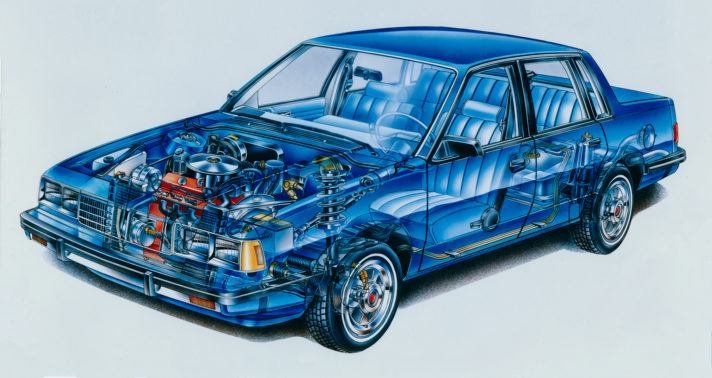

Two assignments I got to both draw and ink, a Chevy Celebrity cutaway for the Shell Car Care book and an Impact Wrench for Ingersoll Rand, which to this date is still the most I ever made for a single drawing project. The project was received on one day and had to be shipped FedEx at the end of the next. So two day turn around and I made a cool $3000 which was a lot of money in the late 80’s.

Working for Dave was never easy. The opportunity it presented was never lost on you, and you always wanted to bring your best possible work. Deadlines were often pretty tight, so there was some stress involved. To balance that, he always paid quickly and well which was a plus, and conversations with him were alway entertaining.

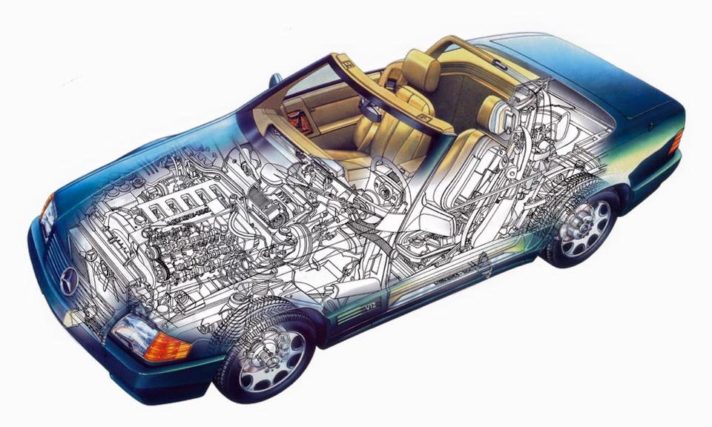

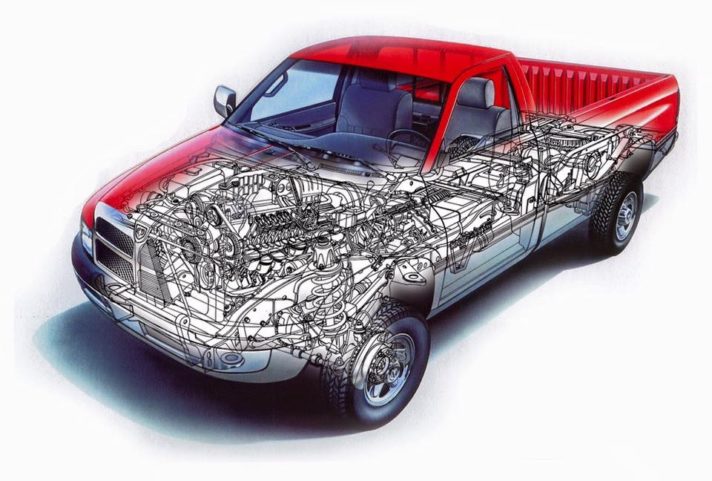

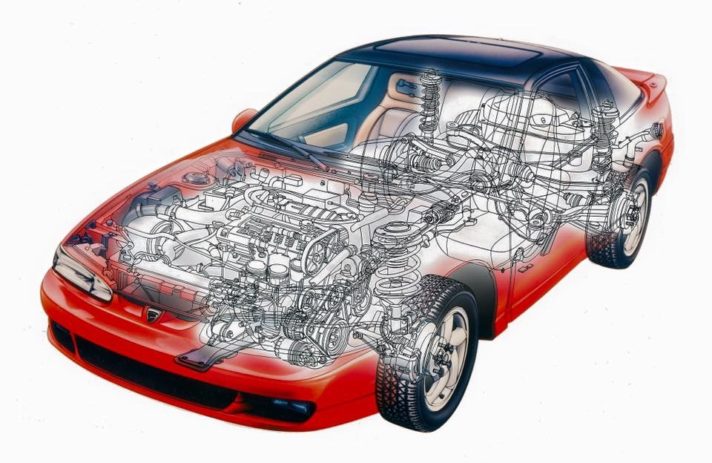

The work slowed down just as my reputation in Detroit was at an all time high. I began to get calls from so many places locally to do work, and many of the conversations started with “We are looking for a Kimble-like cutaway, but we don’t have a Kimble budget…” While Dave was amazing, so were his prices, and again there was a tone of flux in the local economy which simply couldn’t afford his work. I would quickly explain that I don’t paint, and that all I could do was the drawing and line work.

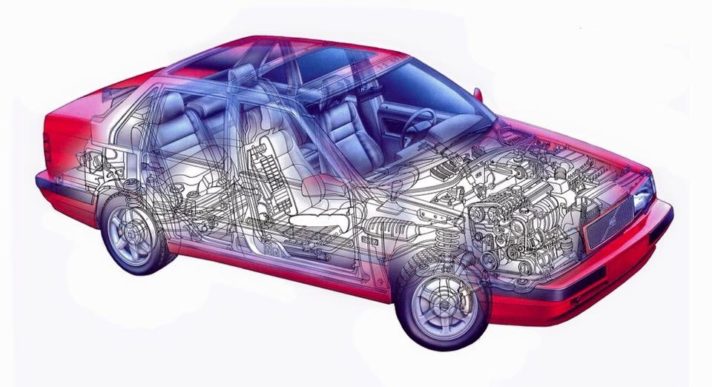

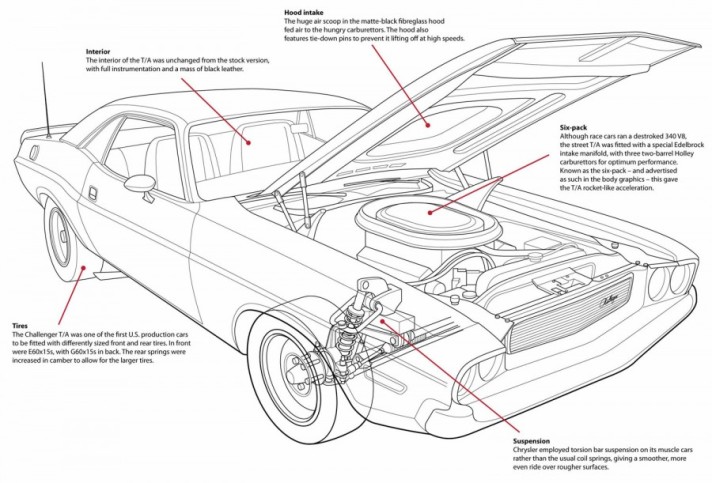

At first I would do some of the simple stuff, but eventually I knew I might be competing with him for the same work. Had his work not dropped off I would have passed on it but I needed to eat and continue to build my reputation in town, so the big hits started to cross my board. Detroit Art Staff got me the Mercedes 600 SL and the new C-Class cars, Combs and Dudeck the Cadillac Seville with Northstar, Iconix the Dodge Ram with 10 cylinder Viper engine, Macnamarra and Associates the Eagle Talon and the latest Volvo.

Eventually the use of cutaways kinda fell of the map in vehicle marketing trading technical details for amenities and comforts.

Your work with Kimble led you to Paramount and your Star Trek work. Talk about your experience working with them.

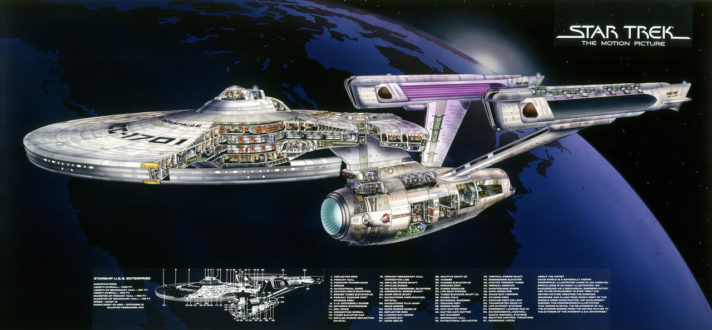

David did the cutaway for the Star Trek: The Motion Picture, which was a massive 48-inch format poster sold in the theatres. I got my first copy at the opening of the film my first year at Ferris. In the back of my head I knew I was on the right career path! I knew one day I wanted to be involved in Star Trek! One of the first things David did for me was send me an autographed copy which still hangs to this day in my home.

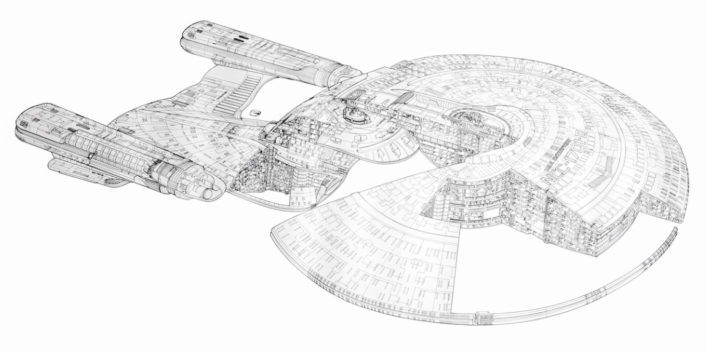

I had shown him an early concept cutaway of the Star Trek: The Next Generation Enterprise when he went through my portfolio and I asked him if he wanted to team up to complete my idea. He said that he was not interested, citing that he had a horrible experience the first time around financially, and was not interested in getting caught up with it again. He did connect me with the Paramount folks and wished me luck.

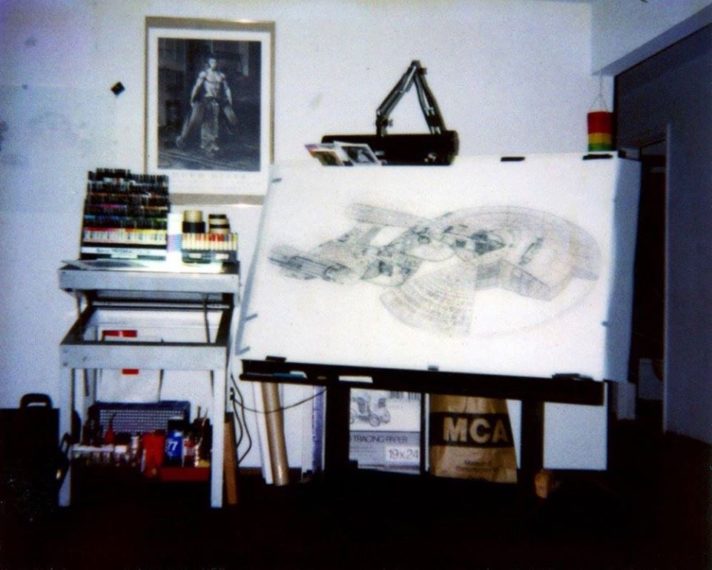

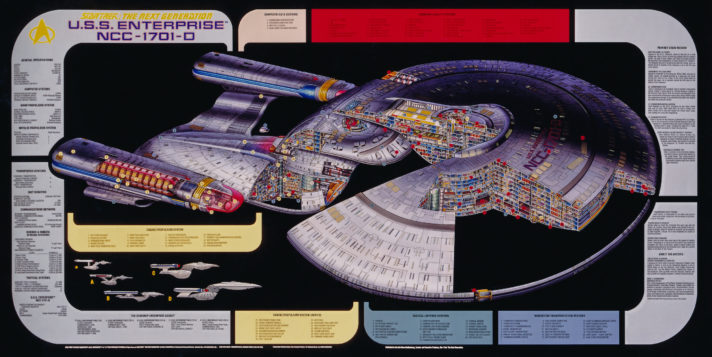

Paramount was really just wrapping its mind around merchandising when I first approached them, and sent me a list of approved poster vendors, who either didn’t see the value or wanted my drawing for a song. I ended up contacting a distributor in Michigan who contacted Paramount and set up the final deal, and in early 1993 my 52-inch poster rolled off the press in Chicago.

The process with Paramount was grueling, in as much as my drawing was submitted to the ST art department and was dissected with a red pen. I made dozens of changes, large and small, which got approved! On completion, a full sized duratrans was sent to the Smithsonian and hangs in their permanent collection.

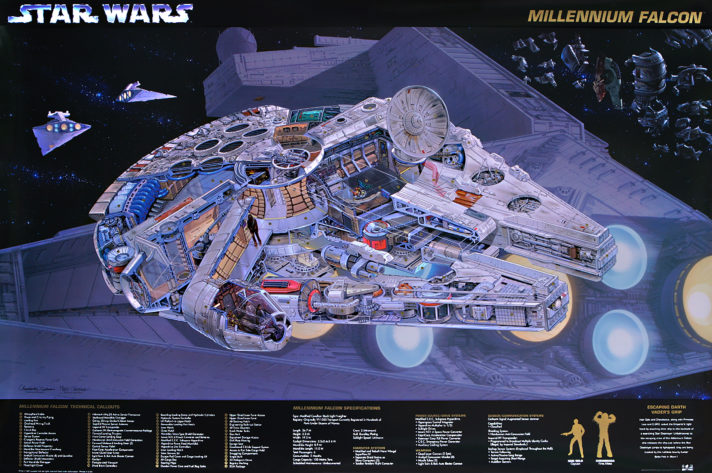

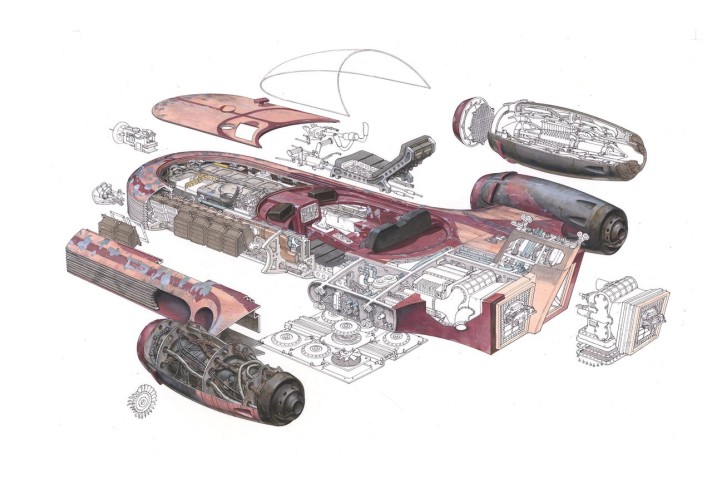

Fortunately/unfortunately the poster was such a hit that it sold hundreds of thousands of copies, and the distributor began to ghost me on my royalty payments. I had proposed a follow-on Millenium Falcon poster concept and that seemed to get ignored as well. I ended up suing them in court which gave me damages, and the added step of pain and suffering, somewhere close to $70,000. The next day I received a register mail announcing their bankruptcy, and there would be no money coming my way. This was my single worse day as an illustrator.

A couple years later while at my favorite art supply and framing store I saw a completed version of my Millenium Falcon poster concept waiting to be picked up from the framer. They explained that I was set up to become a poster but the deal fell through. Not only had they reneged on my Star Trek money, but they took my next concept to fruition and the bankruptcy stopped the printing!

The story was just getting worse by the moment.

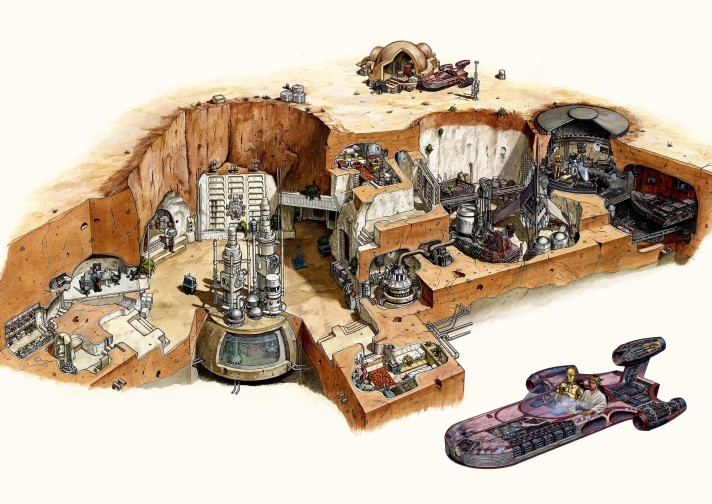

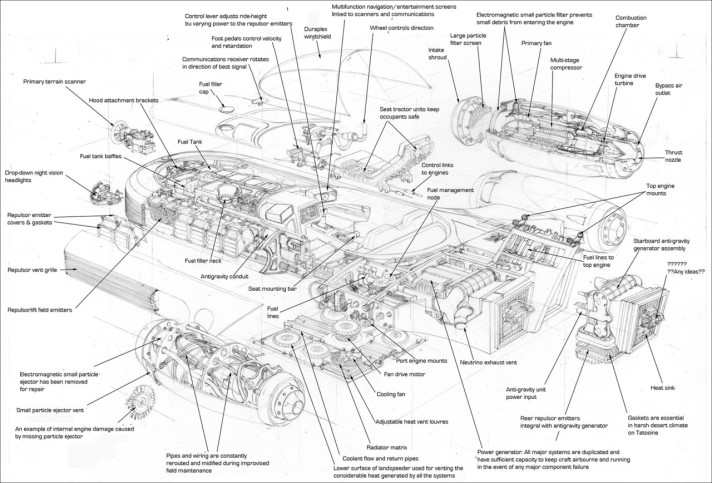

Fortunately, I along with my brother connected with SciPubTech and the Star Wars concepts we created took new life and were completed to coincide with the original trilogy re-release! So in the end, I did prevail.

We ended up creating six new Star Trek posters and three Star Wars posters. One of which, DS9 made it into space! On May 19th, 2000 aboard the shuttle Atlantis/STS 101 an ISS construction flight! The DS9 poster returned 10 days later and hangs in the ISS program office! This amazing experience has shown me that there is no limit how far and high you can go!

You’ve also worked on projects in the Star Wars universe. How did that come about, and what was that like?

When we connected with SciPubTech, I showed them my Millennium Falcon cutaway and talked about the upcoming re-release of the original trilogy in the theatre. So we had a new motivation to do the work.

Our Star Wars posters are unbelievably accurate. Many don’t know this, but the Falcon was slightly different in each film. So my task was to forensically go in and pull them all together into one drawing! Lucas Film was great with providing archived materials for many of the ships. The one thing I am most proud of though, was that we were the first to market with official cutaways. There have been many books since with slightly different takes, but we were the first!

Your brother, Matthew Cushman, is also a technical illustrator. What’s it like collaborating with him?

He is indeed… same degree and under the same instructors for the most part, but 11 years different. His foray into Star Trek began with his final project, where he drew a cutaway of the original series Enterprise. As his big brother, I lent him all my

technical information from my collection. A version of that drawing became our first product at SciPubTech. It was a big hit!

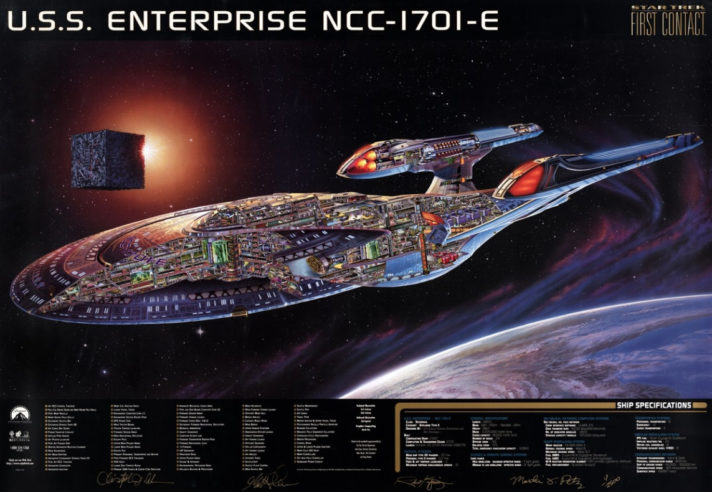

All of the work we did up and through the SciPubTech days was done manually, pencil on paper, ink on mylar, paint on board. In that respect we worked very similarly. Where we diverge is in technique. Matt is fastidious in his pencils, crisp and very clean, if not a bit light. I am more heavy handed, darker, less clean. The ultimate test of detail came when we participated in the redesign of the Enterprise E, which we collaborated on. There were many elements to the project, and while I did the liaison with the art department, collecting the materials and Paramount licensing getting all the approvals, Matt took on the Phoenix drawing for a mini-poster. But we both did half of the Enterprise poster. I, the front saucer, and Matt the rear and engines. When we completed the final pencils, I put the two pieces together and were off by less than a millimeter! It was a most satisfying collaboration.

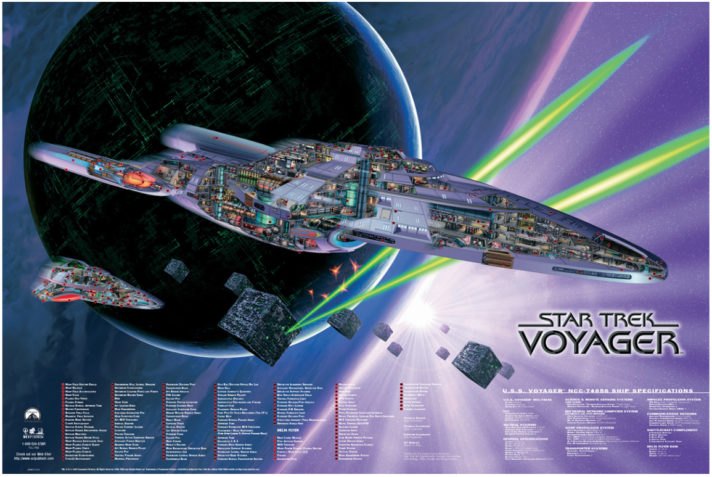

Today Matt is more attuned with Adobe Illustrator because of his client work. I largely stepped away from Illustration after 1998 and my move to Toronto. My final poster was of Voyager and the Delta Flyer. I got a second degree in Design and am back playing catch up in Adobe illustrator.

What would be your dream technical illustration project?

Well, I may have already got that when I worked on the Enterprise E. Our work ran concurrent to the film production, and we were drawing things that had never been seen! My dream of working on Star Trek has kind of been fulfilled.

What are you currently working on?

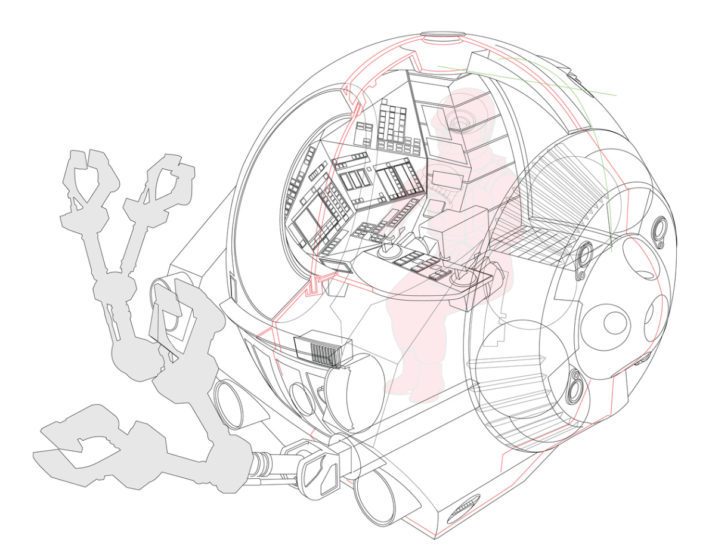

There are a couple new things brewing. A series in book form for Battle Star Galactica (new version) and the ships from 2001: A Space Odessey (I have put a lot of work into the EVA Pod drawing).

I am working on a revised Enterprise D poster. I completed the first one around 1992, or 3rd season, and I want to update it to 7th season and Star Trek Generations.

What advice do you have for students or illustrators starting out?

Build it and they will come. It’s a great time to be an illustrator, but you should set aside time to draw some vanity projects. Things you might not get to do in the real world and draw them for yourself. I did with the Enterprise D and it turned into one of the greatest chapters of my life! Opened many doors and opportunities of work and meeting my heroes….

Dont wait! Just jump in!

Where can people see or buy more of your work?

You can see me on my blog and get a more detailed view of my Star Trek/Star Wars journey. SciPubTech.net still sells a few posters, but you can find others on eBay. I am currently rebuilding my Illustrator web site, coming soon.