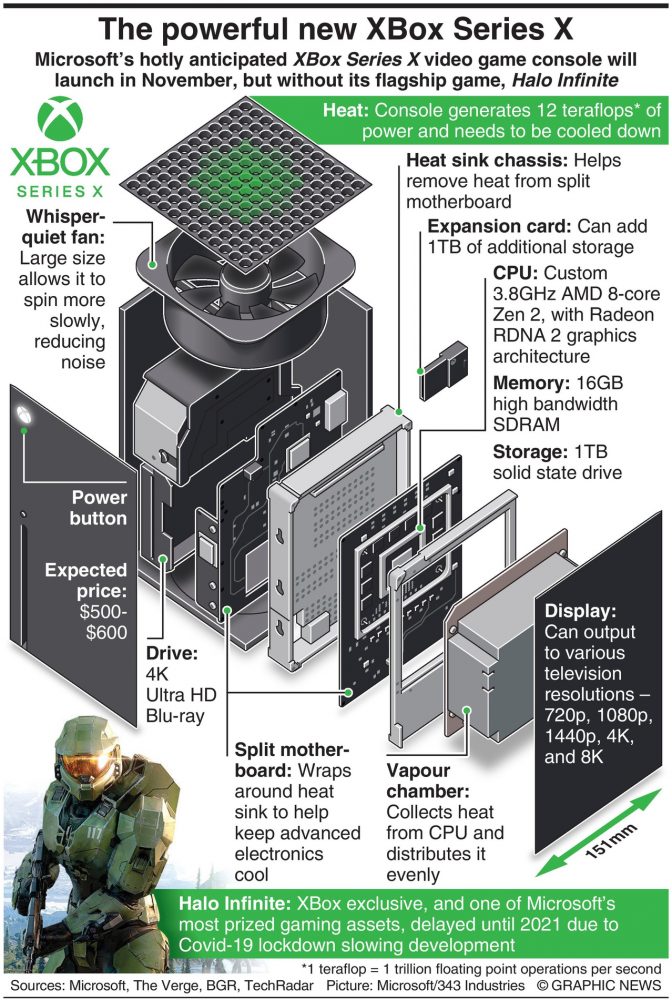

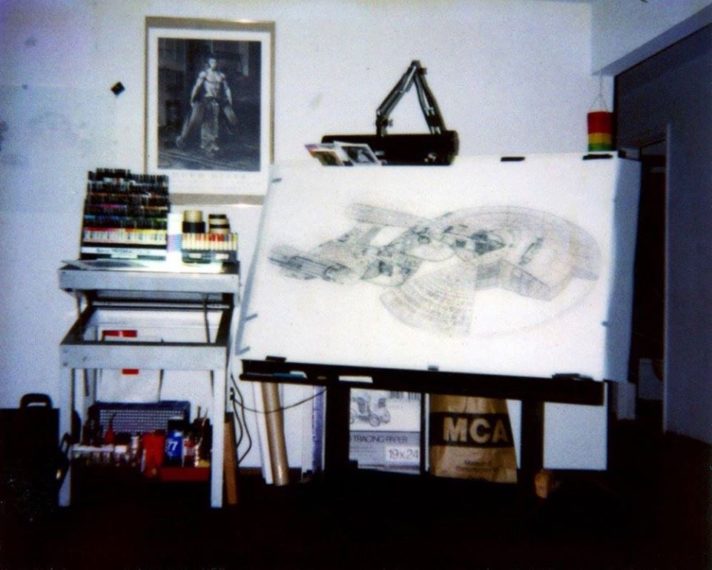

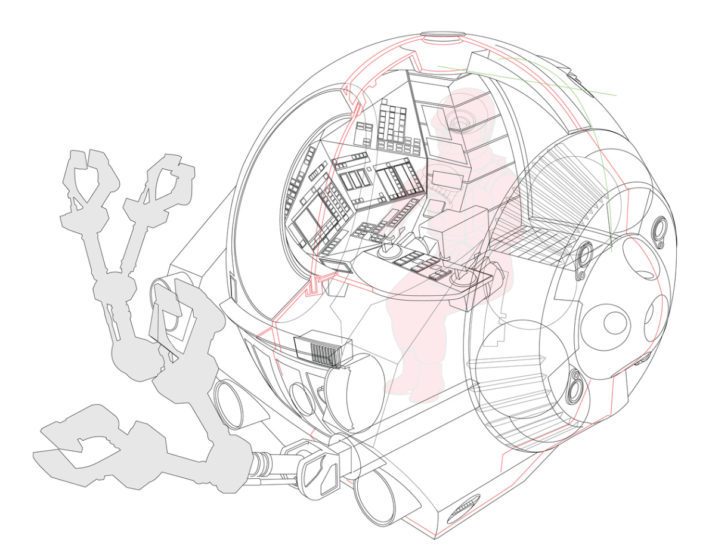

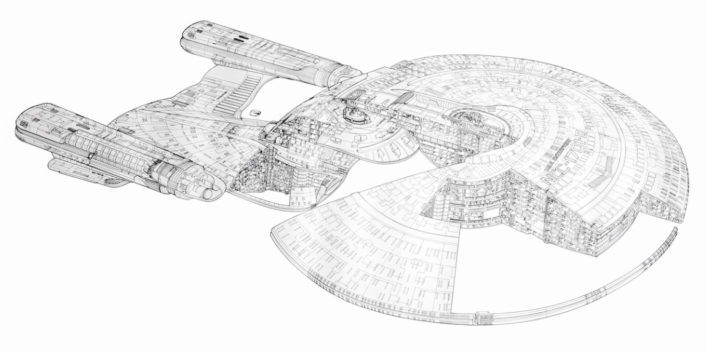

Infographic designer Ninan Carter [previously] has once again documented and shared his process for creating a detailed and technical cutaway illustration. This time, his subject is Microsoft’s upcomng XBox Series X video game console, highlighting the hardware design and capabilities of the new machine.

Check out the whole process on Ninian’s blog, Graphic Gibbon.

Thanks Ninian!