Hans Jenssen is a UK-based technical illustrator with over 30 years of experience. He is perhaps best known for his collaboration with Richard Chasemore on the Star Wars Incredible Cross-Sections series of books. He continues to use traditional methods and materials, pencil, pen, gouache and acrylic paints to create his intricate, accurate and textural images. He is currently working on a new collaboration with illustrator John Mullaney about the Halo video game franchise. He was kind enough to answer a few questions for us.

What brought you to the field of technical illustration?

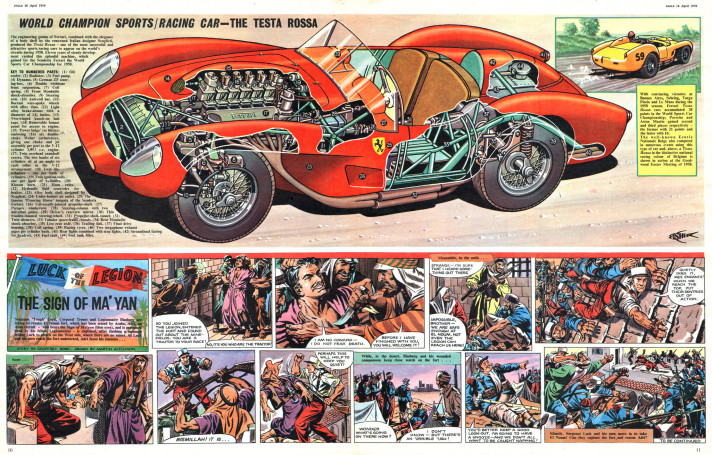

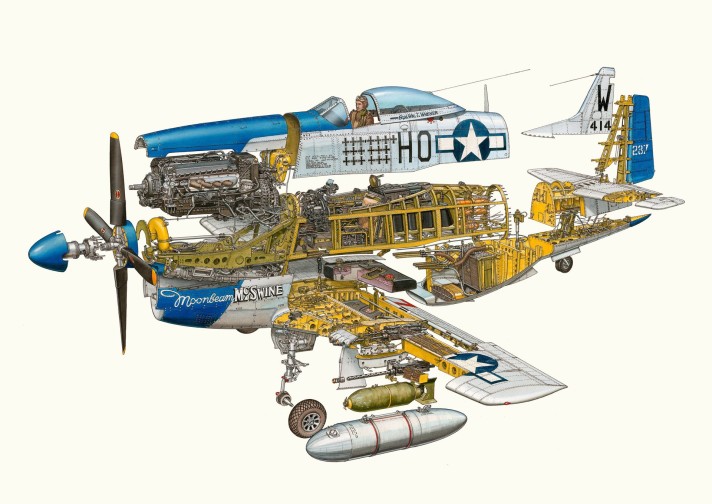

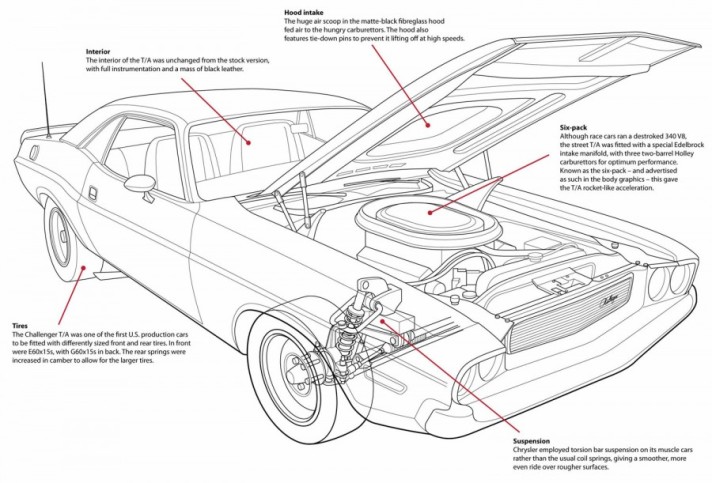

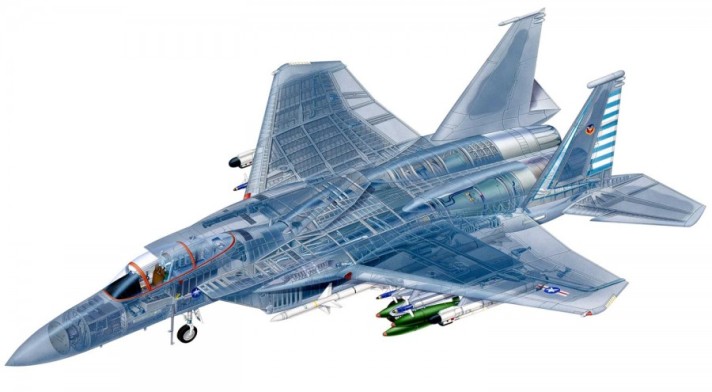

Simple! As a kid I loved drawing and I loved comics like Eagle and Look and Learn here in the UK which featured colour cutaway illustrations. I was always trying to copy them and create my own so becoming a technical illustrator was probably inevitable.

How did you get started with Dorling Kindersley (DK Books)?

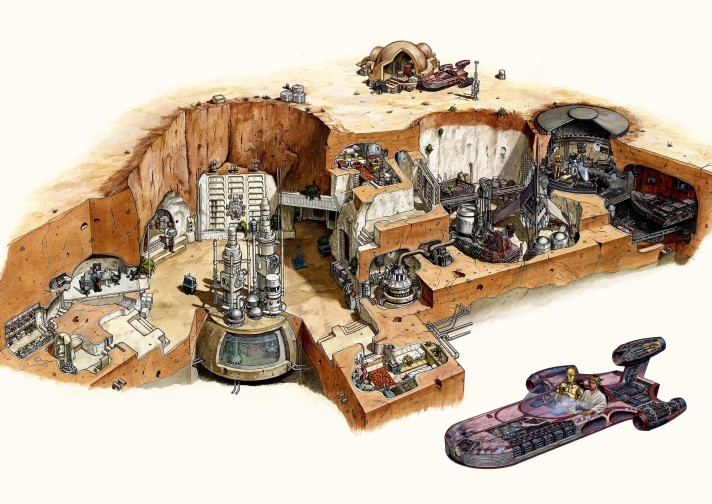

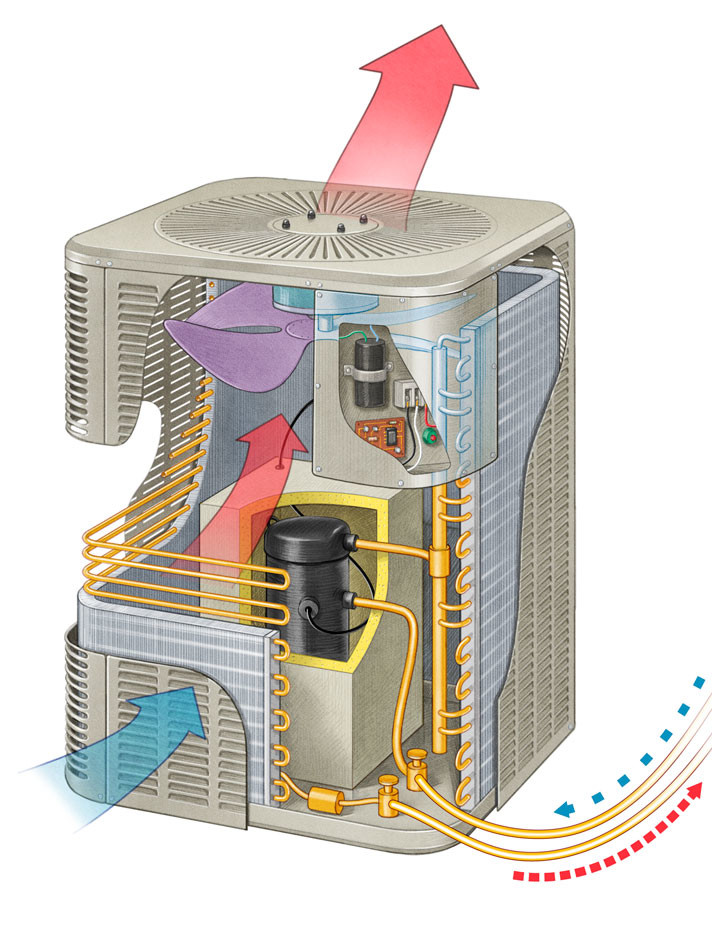

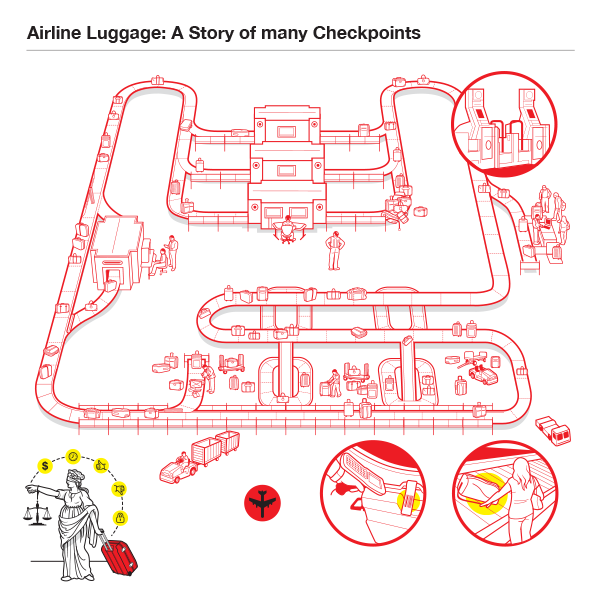

I was represented for quite a few years by the Virgil Pomfret Illustration agency who got me my first job with DK back in the early 90s. It was a good break for both of us as DK kept me so busy all Virgil had to do for a few years was write an invoice now and again. At first I worked on a series called Look Inside Cross-Sections based on the hugely successful Stephen Biesty’s Incredible Cross-Sections. I did three titles and this was when I met Richard Chasemore who also worked on the series and with whom I later collaborated on all the Star Wars books and a very successful advertising campaign for United Technologies in the USA.

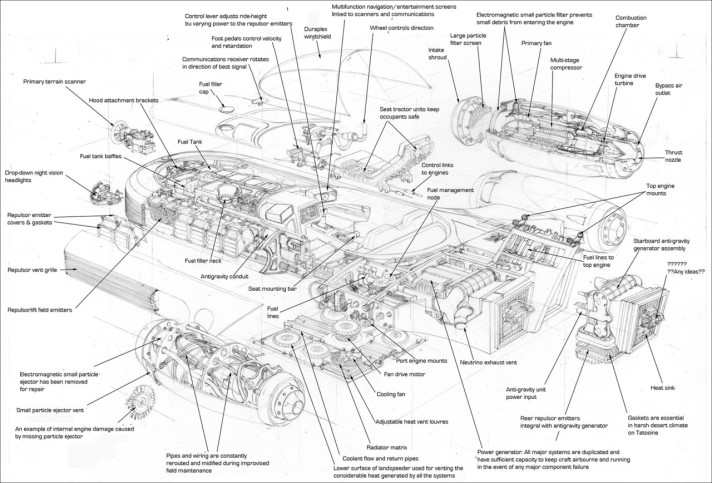

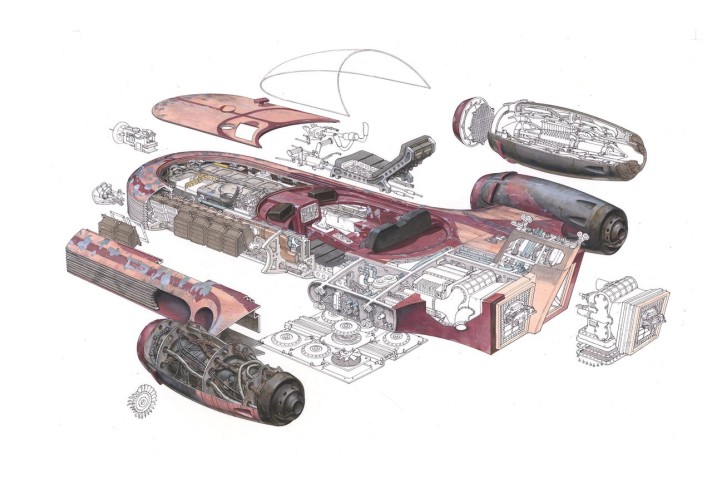

Any unique challenges/experiences working on the Star Wars books?

Gosh, where do I start? Star Wars, with its legions of fans was quite a prospect. When we first started, (working with author David West Reynolds who at the time had a day job at Lucasfilm) we were treading very carefully. Using old reference which clearly hadn’t been very carefully thought through and different sources which often contradicted each other created many challenges. Where there were gaps in the reference we were able to create new technology and machinery and Lucasfilm were so pleased with the results that we were soon redesigning and re-imagining other parts of ships’ interiors to try to make coherent systems which logically explained the abilities of each craft. Parts which were seen in the movies were of course drawn and painted as accurately as possible, right down to the scratches on the paint in many cases.

What changes or challenges have you faced in your career? What opportunities do you see for the future?

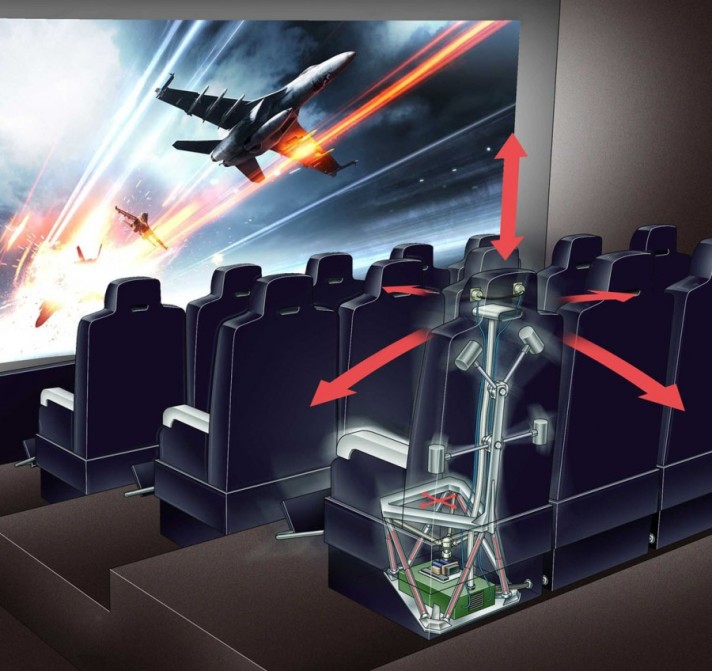

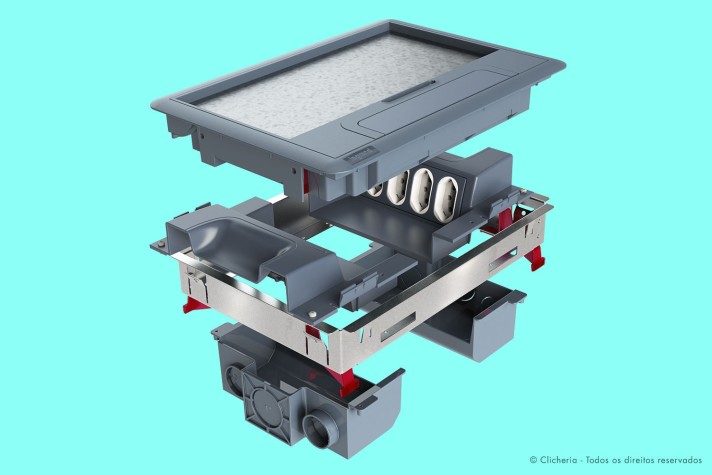

Well, of course, since I started there has been a digital revolution. I personally have never really taken to the computer as a means of creating art but I am the first to acknowledge there are plenty of super-talented digital artists out there who do incredible work. But for me, one of the things I love most about my work is the physical connection between pen and paper, pushing paint around until things look just right, and being able to look at the physical artwork and see the colours, the texture of the paint, the linework, all done by hand. That is such a huge part of the joy for me. Of course, in the old days if you made a mistake, you could be in a whole mess of trouble whereas now with modern digital retouching, no sweat! Of course my stubborn refusal to let go of traditional media does make me somewhat niche in this digital age but I still think there’s no substitute for ink and paint when creating the kind of richly textured colour illustrations I specialize in and thankfully there’s still some work out there. As long as there’s work and my eyesight holds out, I’ll keep going!

Do you have a dream project? Any subject matter that you’d love to illustrate?

If I could choose one thing to illustrate, it would be one (or all!) of the giant Russian civilian and military Ekranoplans from the 1960’s and ’70’s. Ever seen the “Caspian Sea Monster”? Getting reference might be a bit tricky but that would be a dream project.

Do you have any advice for new illustrators or students?

It may be a cliche, but I am always reminded of a Q&A Richard and I did in America some time ago when a young chap asked, “How did you get so lucky that you got to work on Star Wars?” Rich answered, “I’ve always found that the harder I work, the luckier I get.”

See more of Hans’ work at his website and be sure to check out his cutaway illustration process.