This promo video for the just-announced Microsoft Surface Studio really caught my eye, beyond the hardware itself and what it could do in the hands of a tech illustrator. Watch starting at 0:25 at 0.25x speed. It’s not the most informational example of technical communication, but it certainly makes you marvel at the precision and sophistication of the product’s design and assembly beyond what the consumer would normally see.

John Hartman

John Hartman is a technical and scientific illustrator who seamlessly blends traditional media with 3D and digital techniques to create images that are fresh and contemporary, yet warm and inviting. His work can be seen regularly in Fine Woodworking, Woodcraft, Fine Home Building and more. John agreed to answer a few questions about his work and career.

What’s your background? How did you get started in technical illustration?

It’s a long story but here it is in a nut-shell. I have always been interested in drawing and painting. My early education was in fine art. I also found technical illustrations like those in Scientific American, Popular Mechanics and Fine Woodworking inspiring and they appealed to my interest in art, science and technology. Since my school days predated the personal computer, technical illustration was being created strictly by hand. As a student I was impatient, rebellious and seeing how fastidious hand drafting and airbrush painting was I decided to go another route and become a fine artist.

I found myself living in Brooklyn, working odd jobs to pay the rent. Being a starving artist wasn’t for me so I decided to learn a trade. I also had an interest in music as well as art so I re-educated myself as a piano technician. Fast forward a few decades and I am running my own business rebuilding grand pianos. Knowing of my art background the editor of the Piano Technician’s Journal, the trade magazine for people who tune and repair pianos, asked me to come on board as their illustrator. I spent the next six years teaching myself technical illustration. Starting with traditional hand methods and eventually developing digital techniques that emulate the handmade artwork I loved in my youth.

The pianos are now gone and I am working full time as a freelance illustrator. I’ve converted part of the piano shop into my studio, and have kept the woodworking shop as my man cave. I love this work and wish I would have started earlier. There’s a lesson in this somewhere.

You work in a range of styles and subject matter. How do you choose the right aesthetic for a project?

Well I think the right aesthetic is the one that gets the job done and also appeals to me personally. I have never hidden the fact that I work digitally but my personal taste in art and illustration is rooted in traditional analog techniques. So generally I don’t want my work to look like it popped out of a computer program. I think in my case what comes off as different styles is really a result of my penchant for experimenting with a wide range of tools and methods. Typically I may blend together 3D rendering with hand drawing and a little vector work as well. I love learning new software and trying to come up with different ways to create illustrations. Sometimes I attempt to emulate a particular analogue drawing style, the results vary but I always learn something new. For me, it’s more of a challenge to stay consistent and on track. Except for my personal taste, experience, and craftsmanship the style chooses me rather than the other way around.

As you noted, I enjoy working on different subjects as well; there is nothing better than being handed a unique assignment, and doing the research can be fun as well. But I have never consciously linked a style to a particular subject except in the case of my work with Fine Woodworking Magazine where there is an established style. I do try to be consistent within a project and if the art director points me in a particular direction stylistically I make every effort to accommodate. In addition, with art directors I know well I will often discuss style issues to better integrate the illustration with the page design or create something a little different than usual. Some of my most successful work stems from collaboration with a talented art director.

What challenges have you faced in your career? What opportunities do you see for the future?

Projects that are complex or those that require a new skill to pull off, or have a very tight deadline have kept me awake at night. Over time I have learned to expect these sorts of challenges and I find myself looking forward to difficult projects. One challenge we technical illustrators face is keeping up with ever evolving technology, requiring practice and self education. I think learning new software is vital to staying competitive. Also I find I need to brush up on core software I already know like Photoshop and Illustrator. Since software is doing more of the heavy lifting I find I need to practice my analog skills and foundation knowledge like perspective just to keep from losing this valuable tool set.

What I see on the horizon for technical illustrators is the increased use of 3D animation. On-line video is becoming the leading media for news, education and entertainment. It may take some time but eventually publishers, advertizing agencies and businesses will seek out talented illustrators to create information based animations.

Do you have any advice for new illustrators or students?

Technical illustration is a broad field of study. It covers any illustration assignment that needs to show the viewer how something functions or how parts are interrelated. At its heart is clarity and precision, and consequently it requires more discipline and knowledge. I believe students need to work longer and harder to gain the skills needed. New illustrators and students need to know it’s going to take passion and dedication to be successful in this field.

Technical illustrators need to be able to draw well. This means being able to accurately depict the world around us with line, tone and color. Don’t expect to gain this by attending a few classes in school, it will take a lifetime of learning, and continued practice to maintain. You need to study perspective, how to render light and shade as well as color theory. Don’t expect computer programs to do this for you. If you wish to include the figure in your work you will need to study artistic anatomy as well.

Working as a technical illustrator is not a passive act, you are expected to research and understand the topics you are given. In addition you will need to solve the many technical and design issues that arise with each assignment. The artistic quality of your work is up to you. Hopefully you have a passion for fine art and can bring flair to your work that is attractive. I believe that technical illustration should be beautiful as well as useful.

See more at Hartman Illustration.

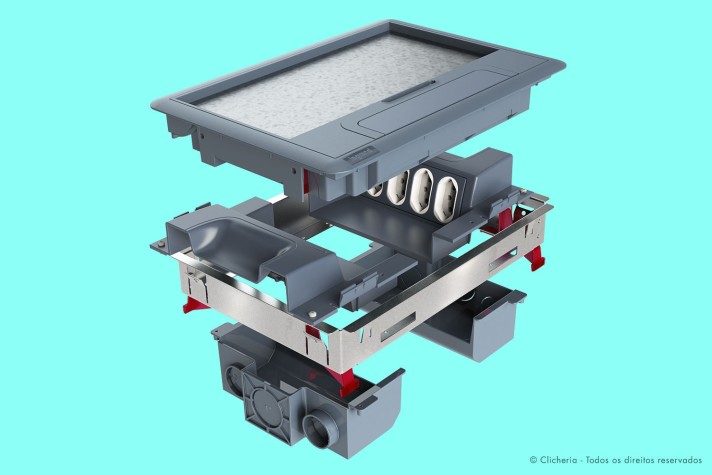

Smartphone Isometric Illustration Process

Infographic artist Ninian Carter (previously) has shared another step-by-step isometric illustration process, this time of a modular smartphone and its interchangeable internal components.

Check it out at his blog, Graphic Gibbon.

Mark Franklin

Mark Franklin is a London-based freelance technical illustrator. During his 30-year career, he has illustrated a wide variety of subject matter for clients including Airfix, McDonalds, Tekmats, Rowe Hankins Ltd. and some of UK’s largest publishing houses.

Check out Mark’s portfolio to see the breadth of his work: Mark Franklin Arts

Todd Detwiler

Todd Detwiler is the Design Director at Popular Science magazine and an accomplished illustrator in his own right. At PopSci he is responsible for fusing design, photography and illustration with stories of science and technology’s bleeding edge. As an illustrator he brings his technical aesthetic to the pages of TIME, ESPN and Washingtonian.

What’s your background? How did you get started in editorial design?

My junior year of college I secured an internship with Maxim magazine. It was the result of a funny letter I wrote to the then-art director David Hilton – who got a kick out of the flippant humor and gave me a call. I had interviews at Details and Rolling Stone as well, but Maxim offered me the internship and I moved from rural PA to New York the next week.

I was really at Maxim at the right time. Felix Dennis had brought his lad-mag over from the UK and it was lighting the magazine world on fire. It was there that I met people who would shape my career in magazines and illustration. I graduated a year later from Kutztown University and started working for Maxim full-time. Along with some junior design work, I was the resident icon artist and occasional spot illustrator. I was cheap (free) for the company, and I was just happy to have some work in print. It was a win-win really.

In 2005 I left Maxim and started working at Rolling Stone before being offered an attractive Art Director position with Hearst working on the development of a new Men’s Magazine. The project didn’t pan out and I started a freelance design career which took me around the publishing houses of New York and abroad until I settled down with Popular Science in 2011.

What do you do as Design Director at Popular Science?

As the DD of Popular Science, I led the team responsible for the 2014 redesign, along with an overhaul of the logo and brand guidelines. On a day to day basis, I do all the typical art department work loads – hire illustrators, design pages for features and front of book, brainstorm photo concepts, etc. It’s a small but talented art team at Popular Science – and I give them a lot of credit for making the magazine smart and efficient.

What makes for a good illustration? What can illustration do that photography can’t?

The best illustration communicates an idea quickly and clearly with some personality. I would also add that the process of commissioning the illustration makes it a “good” illustration. If deadlines are met and the work matches what is expected – that makes everyone’s life easier.

Photography can be expensive. With an illustration you can build a world that is immersive at a fraction of the cost. You can also build uniformity with illustration that can be a struggle with photography if you are using pick-up art from multiple sources. Both have a place in Popular Science, and we are very conscience of the balance in every issue.

What do you think makes the technical illustration aesthetic so popular in magazines?

Well, it’s been around for awhile, hasn’t it?! I was just looking at an instruction manual from the 60s the other day that was amazingly drawn. My hat goes off to the illustrators that were so meticulous with ink and pen. It’s a lot easier with a mouse and “command+z”..

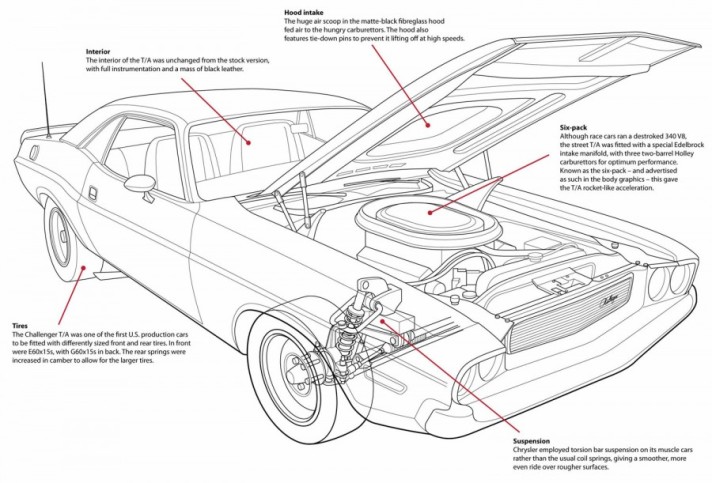

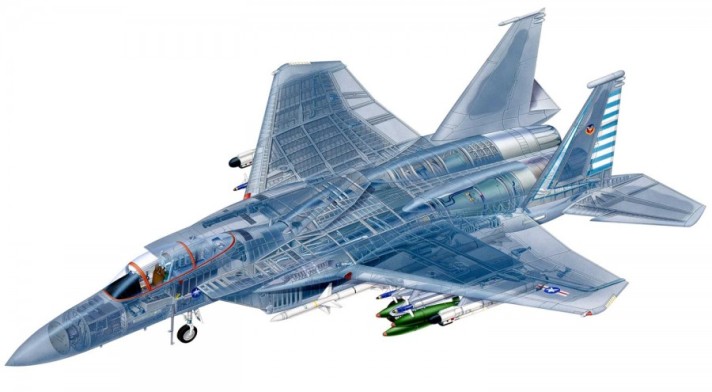

Regarding the aesthetic, I think the thick rules on the outside give the objects separation and weight, and the thin lines detail and clarity. People love exploded views because they can see what’s happening on the inside – something the PopSci reader loves. Ultimately, I think the style of illustration removes clutter and anything unnecessary to reveal the essence of the subject. It circles back to direct communication, free of any additional interpretation for the viewer.

In addition to your role at PopSci, you also moonlight as an illustrator. What drives you to illustrate?

I love illustration as much or if not more than editorial design. But what actually drives me to create illustrations is seeing the work of others. I’m constantly impressed with the level of design being generated by artists, and I can’t help but be inspired to create and learn.

What do you see for the future of publishing or illustration? Any advice for new illustrators or students?

The future of publishing is digital with print declining over the next 5 to 10 years. Illustrators need to be quick and consistent. I see enormous opportunity for illustrators in the digital News sphere. When breaking news happens, how fast can you turn out an editorial perspective, or even better – a comprehensive breakdown of what has happened or is happening. The world demands answers immediately and if you can act quickly, you’ll be very successful. Also, take your phone out of your pocket – that’s your new canvas – get used to it!

You worked with Graham Murdoch on the Electric Racecar project for PopSci. What was that like?

He’s just the best. I’ve been working with him since the Maxim days and he has always made me look good. For the Formula E assignment I sent him a bunch of scrap art and he was able to build out the entire car based on the reference I sent along with his own research. When it came to “exploding” everything apart, I know he spent a lot of time meticulously unscrewing every bolt and washer. The result was amazing, and it set the bar high for everyone in the magazine.

Big thanks to Todd for his time. You can find his work at ToddDetwiler.com and on newsstands everywhere.

Vic Kulihin

The vector illustrations of Vic Kulihin are fresh, bold and contemporary. So you might be surprised to learn that his freelance career began in 1988. Vic was kind enough to answer a few questions about how the industry has changed in that time and give a few tips on having a long and successful career.

What’s your background? How did you find your way into illustration?

I started out as an engineering major at Rutgers University, but graduated with a degree in art education (long story). After college I worked as a paste-up artist for a small ad agency, which folded not long after I started. I then found a position as a technical illustrator for Bell Laboratories. This was back in the day when we used airbrushes, technical pens, straight edges, French curves and typesetting machines. During my stint there these tools were gradually replaced with Macintosh II desktop computers using Adobe Illustrator 88 software.

After a decade I left Bell Labs to start my own freelance business. The timing was right. I was able to combine my work with being a stay-at-home dad for my baby daughter. At that time I focused on colored pencil illustration, but eventually gravitated back to the Mac and vector art.

Earlier in my career I took classes at Parsons, the School of Visual Arts and the Art Students League of New York to make up for my lack of formal art training. I still take classes periodically, but the beauty of it nowadays is that they are readily available online.

What is your favorite subject matter or type of project?

Although I’ve had the opportunity to draw a great variety of things, I think my favorite subject matter has always involved mechanical devices…tools, machinery, that kind of thing. I enjoy creating assembly instructions, exploded diagrams, cutaways, schematic drawings (I think I’ve always been an engineer at heart).

What’s your process for a typical project?

I start with a thorough discussion of the project with the client: project specs, style, number of iterations of sketches/final art, timeframe, budget, etc. When the project involves a product I ask the client to supply me with reference photographs and, whenever practical, the actual product itself. For projects involving people I will often photograph live models and/or use software like Poser or DAZ.

I currently work on a Mac Pro with a 30” Apple Cinema Display; I also have a Wacom Intuos3 tablet that I use infrequently (oddly enough I feel most comfortable wielding a mouse). Software of choice is Adobe Illustrator.

Tools like Skype and GoToMeeting have allowed me to work closely and “in person” with clients globally, something I never would have envisioned when I first started out.

You market your services in a number of illustration directories. What has been your experience with that?

I find that of all the portfolio sites I use the majority of my work comes from three directories (theispot, Directory of Illustration, Workbook) and the assignments from these have covered the gamut of illustration. The income that results from these projects generally justifies the expenditure for these sites. I also periodically do a direct mailing campaign. Recently I’ve expanded my online visibility and interactions through social media such as Behance, Twitter, Facebook and LinkedIn.

You’ve been illustrating for 27 years, what do you think makes for a long and successful career?

The biggest challenge has been dealing with the “feast or famine” syndrome…drumming up business when things are slow, or trying to deal with the onslaught when things get very busy.

As for the future?… For some years it seemed like photographs and video were “where it’s at”. But I’ve noticed more recently a big increase in the use of illustration across media.

That’s great news for the likes of us!

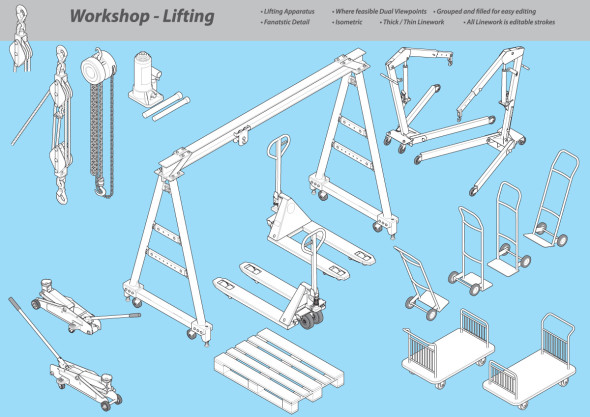

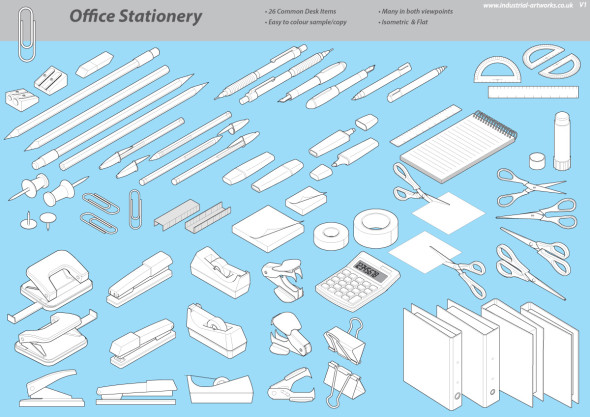

Isometric Illustration Libraries

Matt Jennings has been hard at work adding to his stock technical illustration component libraries [previously]. New libraries include Workshop – Lifting, Workshop – Automobile and Office Stationery. The illustrations look well constructed, have great line quality, and are super affordable at £7.50 to £10.00 ($12 to $15 USD). If you have a relevant project, these could save you a huge amount of time.

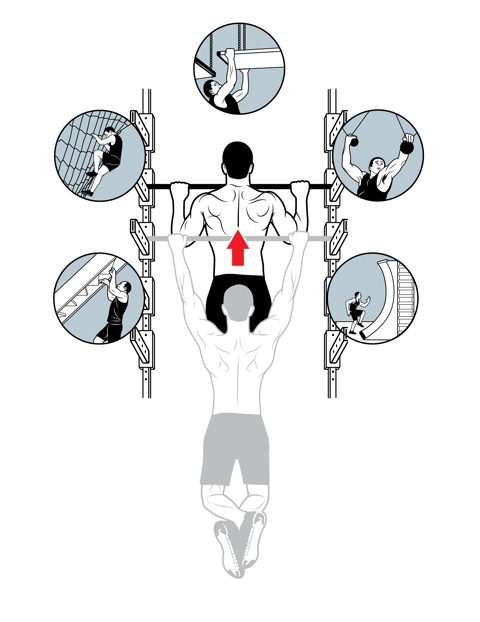

Chris Philpot

Open any magazine on the newsstand and inside you’ll likely find an illustration by Chris Philpot. He creates humorous how-tos, conceptual illustrations, infographics and animations for some of the biggest and best, including Time, Wired, Popular Science, Outside and Men’s Health .

I got in touch with Chris to ask him a few questions about his work, how he got his start in illustration, and what the future may hold.

What’s your background? How did you find your way into illustration?

I wanted to be an illustrator in high school but read articles from practicing illustrators predicting the demise of the profession. I decided I should get a degree in design to ensure a more stable income. That lead me to a job as an editorial art director for about 12 years. While I grew to enjoy design, I still really wanted to illustrate so I started freelancing on the side. Five years of moonlighting gave me enough of a base to make the switch. It was a scary transition, but my wife was incredibly supportive. I’ve been illustrating full time for the last six years. It’s been great. I make more money, have more autonomy and am much more fulfilled creatively.

What are your favorite subjects or types of project?

A technical approach is surprisingly versatile. You can add a subtle joke to dry stories. You can take irreverent or taboo stories and make them presentable to polite society. You can take a really funny story and the art can play the role of the straight man. I read a lot of Gary Larson cartoons growing up and would turn every job into a one-panel Far Side cartoon if I could. My favorite types of projects involve subjects that are fun to draw like monsters, robots and octopuses.

Your style is really consistent, how important is that? How did you develop your aesthetic?

The consistency comes from a few places. Mostly, I need to produce a lot of work to meet my income requirements each month so the volume dictates a certain formula. I try to improve with each job. If a new technique works, I add it to the list of best practices. I’ve also found that art directors are coming to me for the work they see in my portfolio. If I send something too different they often direct me back to the look and feel of my portfolio (I still send in variations if I think they’re better.) I also use a lot of 3-D models for reference. That definitely adds to the consistency, especially in the proportions of people. I’m pretty lanky so using myself as reference wasn’t working out.

What’s your process for a typical assignment? What hardware and software do you use?

I take the brief from the client and request any missing information like story details, budget and schedule. I try to get as close as possible to a final draft by the sketch deadline. It puts the art directors and editors at ease and I think everyone is more inclined to approve things. Revisions hurt profits and the end of the time line breeds a revise-happy anxiety. This is sometimes unavoidable of course.

Regarding software, I use a lot of inexpensive models from Daz3d and Turbosquid for reference when I can and trace the renderings out of Poser or Blender with Illustrator. For hardware, I buy a top-of-the-line iMac every 4 years and use a Wacom intuos4. The tablet was the single best addition to my work flow. I’m not sure how I ever drew with a mouse.

Animation started in Flash but is now done exclusively with After Effects.

What challenges have you faced in your career? What opportunities do you see for the future?

Transitioning from a full-time job to full-time freelancer was a challenge. I worked a lot before going to the office, during lunch breaks and after I got home. Now my biggest issue is working from home with three kids. I love being available for them and I need to be productive so it’s a balancing act sometimes.

There are always opportunities for illustrators to pitch or generate their own content. When the iPad came out, everyone in the editorial world started experimenting with video for the app version of their magazines. I’ve always toyed with motion so it was a good opportunity to try something. The business etiquette series for Entrepreneur magazine (written by Esquire Articles Editor Ross McCammon) was supposed to be a simple illustration with some movement. I asked if I could take on the larger sidebar and to their credit they let me try. Once the longer video was approved they agreed to a fee I proposed. I asked a friend and former coworker Tyrrell Cummings if he would help me with the storyboards. It came together nicely and we’ve done a one-to-two minute short video each month for the last three years.

You’ve worked with some of the biggest and best clients. Any tips for illustrators starting out?

It was uncomfortable at first, but I put myself out there with an online portfolio and 4 x 6 postcards. I was turned down by representatives so I had to go it alone. The initial images were primitive. I did jobs for friends and for the in-flight magazine I worked for at the time. That gave me enough of a portfolio on which to build.

If you’re starting out, just keep producing the work you’re excited about and make it visible. Keep updating it. The days add up, and if you stay active you’ll get somewhere. I didn’t enjoy instant gratification but I did get eventual gratification.

Chris’ work can be found at ChrisPhilpot.com

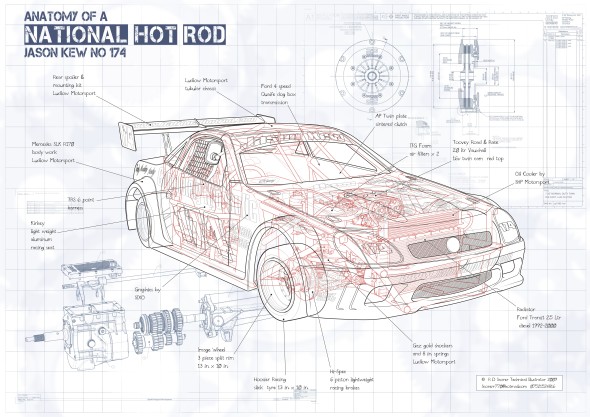

Roy Scorer

Roy Scorer’s portfolio is a mix of historic and modern race cars, as well as livery design and miscellaneous technical illustrations.